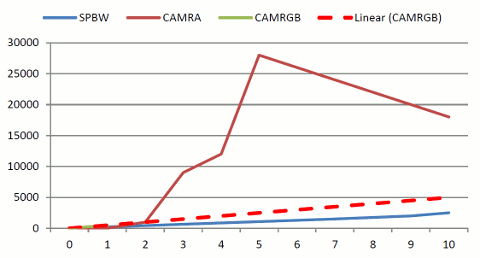

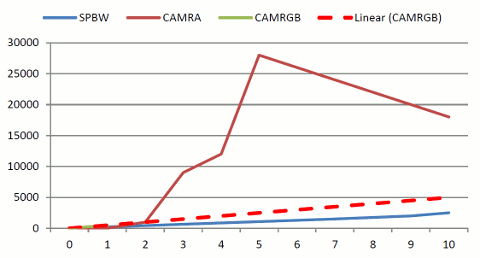

The chart above shows membership numbers for the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA, from 1971), the Society for the Preservation of Beers from the Wood (SPBW, from 1963) and the Campaign for Really Good Beer (CAMRGB, from 2011). It’s based on actual data for the first ten years of the life of the SPBW and CAMRA, as given in newspaper articles, and for the first year of CAMRGB. The red dotted line projects CAMRGB’s membership on a linear course, assuming it continues to grow.

You’ll note that CAMRA wins, so far.

If CAMRGB wants to avoid being an SPBW and instead emulate CAMRA’s early success (which it might not) what do its leaders need to do?

1. Avoid vague objectives and changes of course. The SPBW took an initially hardline stance — wooden casks! — which it then watered down. Their stance was never clearly articulated. When pushed, their president would admit that he wasn’t that fussy about beer.

2. Keep it simple. CAMRA started out as a campaign for good beer and against bad beer, with no clearer definition than that. The focus on cask beer emerged towards the second year after the founders visited some pub cellars and asked a few questions. It was dogmatic, yes, but it was an objective that could be expressed in a single sentence.

3. Get some journalists on board. Three of CAMRA’s founders were journalists and more came on board in the first couple of years. They knew how to write great press releases, grab attention and had contacts in the right places.

4. Democratise and minimise the cult of personality. CAMRA’s founders are still occasionally wheeled out even today, but Michael Hardman handed over his role as Chair in 1973, only two years after getting the ball rolling. There was a healthy turnover of committee members from then on, keeping things fresh.

5. Get a corporate sponsor. CAMRA had some solid support from John Young of Young’s brewery, and then later from other regional brewers. Their patronage put money in the campaign pot and gave CAMRA officials time to devote to the campaign. If Brewdog could be trusted to take a back seat, they might be good partners, or perhaps the quietly massive Meantime? UPDATED 18:10 7/9/2012.

6. Be ambitious in engaging the consumer. CAMRA began publishing a newsletter (What’s Brewing) in 1972; the Good Beer Guide in 1974, when the Campaign was only three years old; and launched their first national beer festival in 1975. The SPBW engaged government and annoyed brewers, but did little to talk to drinkers.

7. Be lucky and seize opportunities. There was a buzz about beer in the mid-seventies which CAMRA latched on to. Their big bump in membership c.1973 coincides with the publication of several books on beer and pubs and the launch of Richard Boston’s column in the Guardian. Mind you, there’s a bit of a buzz about beer now…

8. Support regional activism, don’t get sucked into London. The SPBW has regional branches and little central control, but the bulk of its activity was London-based. City of London based, in fact. CAMRA, being founded in the North West, by northerners, and with its first regional branch being founded in Yorkshire in 1972, was much more in touch with life outside the capital from the off. London CAMRA is just another (big) regional branch.

Disclaimers: we’re still members of CAMRA but haven’t yet taken the leap to join CAMRGB, though we watch its progress with interest. It currently has c.500 members and c.2500 followers on Twitter. It is still free to join but accepts donations.