In 1987, a pub-owning entrepreneur looked at British brewing and decided it wasn’t working.

Stylishly packaged ranges of bottled beers trumpeting their purity and quality are easy to find these days. Back in 1987, though, bottled beer meant, in most cases, brown or light ale gathering dust on shelves behind the bar in pubs, with labels that appeared to have been designed before World War II. If you wanted to know their ingredients, or their alcoholic strength, tough luck, because the breweries didn’t want to tell you.

A cult beer from Cornwall would play a major role in changing that scene.

* * *

Having weathered the brewery takeover mania of the nineteen-sixties and seventies, West Country family brewery Devenish was a strong presence in the region, with more than 300 pubs from Wiltshire to Penwith.

It was also a household name, at least amongst anyone who had ever taken a seaside holiday in Dorset, Devon or Cornwall. Nonetheless, in 1986, the company was struggling. They had been forced to close their brewery in Weymouth, Dorset, late in 1985, thereafter concentrating operations in Redruth, Cornwall. At the same time, they had also closed fifteen pubs. Profits continued to tumble.

Depending on how you look at it, Devenish was either in need of rescue, or vulnerable to predators.

* * *

Michael Cannon was born in Bedminster, Bristol, in 1939, and left school in the nineteen-fifties (according to most accounts) ‘barely able to read and write’. He worked as a poultry farmer in Avonmouth before entering the hospitality industry as a chef with the Berni Inn chain. Then, in 1975, he bought a stake in a pub in the centre of Bristol – the Navy Volunteer – and began his ascent to the rich lists.

By 1986, he was the boss of Inn Leisure, which owned around 40 pubs in Bristol and surrounding areas.

Cannon saw in the struggling Devenish, and especially their more than three hundred West Country pubs, a perfect opportunity. In February 1986, Inn Leisure and Devenish ‘merged’. Cannon’s company put £35m into Devenish to secure a controlling share, with the support of Whitbread’s investment arm. After some initial confusion, it became apparent to most people that this was a takeover by the smaller operation which, in one swoop, took the total number of pubs under Cannon’s control to almost 400.

People who worked with Cannon describe him as ‘a dynamo’, ‘dynamic and intense’, and he has described himself as having a ‘low boredom threshold’. Journalists calls him ‘colourful’. Looked at as a whole, his career in pubs and brewing suggests a complete focus on achieving profit, without the slightest sentimentality. Newspaper headlines, perhaps inevitably, tend to refer to CANNON FODDER or CANNON FIRE.

On taking over Devenish, he set about rejuvenating the company with vigour. First, feeling that they were paying too little rent, he evicted many sitting pub tenants, replacing them with his own managers. Then, in July 1986, news came of the resignation of board member Bill Ludlow, a member of the former controlling family, in the wake of a ‘clash over policy’.

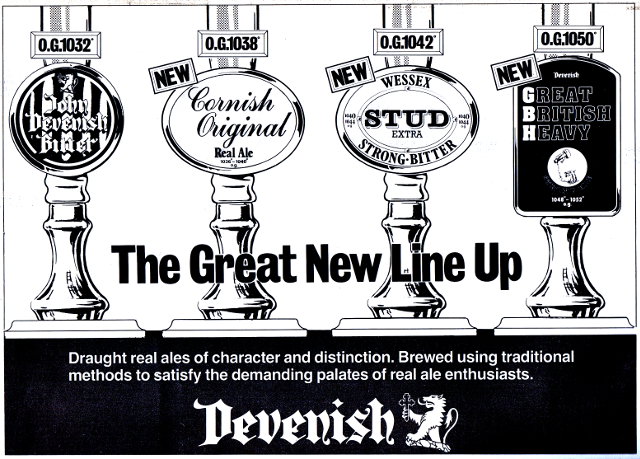

Having asserted his dominance, Cannon also set about revamping the uninspiring range of rather too-similar, middle-of-the-road beers produced by Devenish. Cornish Best and Wessex Best, both the same strength, were made weaker and stronger respectively, while the latter was given a ‘saucy’ new name: Wessex Stud. It was joined by a much bigger beer called Great British Heavy. West Country branches of the Campaign for Real Ale very much approved, though they remained anxious about Cannon’s plans for local pubs.

But that wasn’t enough for Cannon: he wanted a slice of the burgeoning ‘designer beer’ market, and knew that the name Devenish, with its suggestion of dusty old country pubs and deckchairs, was never going to cut it. In the first instance, he renamed the brewing arm of the company (the Redruth operation) ‘The Cornish Brewery Company’, and there was more to come.

According to Paul Hampson of design agency the Hampson Partnership, who worked closely with Cannon on the design of this new brand, it was a trip to America, and exposure to the growing US ‘craft beer’ scene, that provided the necessary inspiration. Cannon was particularly impressed, Hampson believes, by Anchor Steam, the flagship beer of Fritz Maytag’s revived Anchor Brewing.

Anchor Steam was one of the first US ‘craft beers’ to find favour in the UK from the late seventies onwards, primarily among CAMRA members, and under the influence of Michael Jackson. Despite its attractive packaging and interesting brewing process, Anchor Steam is not overly aromatic and a familiar brown colour – in other words, exotic and yet also accessible to British drinkers brought up on best bitter and Fuller’s ESB.

Having decided that, somehow or other, ‘steam’ needed to be part of the story of his new beer brand, Cannon next decided to imply a more glamorous place of origin than the mining town of Redruth where it was actually to be produced. In the late nineteen-eighties, Newquay, in North Cornwall, was about as near as the UK got to the Californian beach culture, famous for its world-class surfing and increasingly popular with young holidaymakers. And so the name Newquay Steam Beer was born.

But what, apart from a snappy name, would be its unique selling point?

* * *

Unsure where to direct its energies after the Big Six brewers had relented and reintroduced cask ale to their ranges in the late seventies, CAMRA had been campaigning on various fronts.

One particular hobby horse was ‘pure beer’, brewed without additives. Founder member Michael Hardman’s 1978 coffee table book Beer Naturally set the agenda. The ‘pure beer’ baton was picked up by fellow founding member Graham Lees who, having moved to Germany, became convinced that Britain needed a version of the German Rheinheitsgebot beer purity law; and also by beer writer Roger Protz, who had written something of a pure beer manifesto, Pulling a Fast One, in 1978.

In 1986, ‘pure beer’ was finally made a CAMRA priority, and, throughout that year, the Campaign renewed its efforts for clearer labelling of beer ingredients and the banning of ‘additives’. Then, either in response to CAMRA’s lobbying or simply reacting to the same external influences, towards the end of 1986, Samuel Smith’s of Tadcaster launched ‘Natural Lager’. Acknowledging the influence, a spokesman for Devenish said: ‘There’s a growing market for healthy foods. Sam Smith’s have produced a bottled natural lager, but why not have a complete range?’

This ‘health food’ image might have been sufficient to make a success of Newquay Steam, but Cannon was also determined to go all out on the packaging and presentation. Paul Hampson:

[Cannon] had very firm ideas as to how the label for his new Steam Beer range would look and there were very few of the graphic devices associated with beer labelling that were left out. Had we been handed an open brief, we might well have created a label less complicated, but this wasn’t the time for that. We did however, ensure that all the elements of the design were beautifully crafted, from label cut-outs and bottle shape, to the woodcut illustrations, hand lettering and typography.

One design feature that would come to define the image of Newquay Steam Beer was its ceramic ‘Grolsch-style’ swing-top:

I recall presenting our first bottle top sketches to Michael, the result of which was a long silence. Didn’t I know how much more expensive the ceramic top would make this new product and wasn’t I aware of the potential cost saving of a standard metal cap? He then approved our ceramic top design and instructed us to forge ahead with production without delay.

Cannon’s nose for what would make money was infallible. Those stoppers, and complete transparency about ingredients and alcohol content, helped the brand stand out in a market place where beautiful-looking bottled beers were then few and far between.

* * *

Will Wallis worked at the Redruth Brewery from 1984 to 2004 and was involved in quality assurance on the Newquay Steam beers. He recalls that the workforce was enthusiastic about the product and just as determined as Cannon to make it succeed.

As a proud Cornishman I felt proud to have our ‘own beer’. There was a lot of hard work put into the beer by a very excited workforce. We believed that Steam Beer was unique on the market and stood a good chance of being a success. Personally, I can remember working twelve hour round the clock shifts with my colleagues who really believed in the product and put in a lot of effort to help launch the brand and make the whole thing a success.

Head brewer Tony Wharmby spoke to CAMRA’s What’s Brewing in July 1987:

[We have] had to completely reorganise our operation… The water isn’t Burtonised, no additives to help clarification or speed the process, and the need to double ferment all have their challenges. The major operational factors are the maturation time, which is weeks rather than days, and the new labelling plant to accommodate the bottle shape and complexity of the labels.

As Will Wallis recalls it, it was a sign of Wharmby’s genuine belief in Newquay Steam that he allowed his image to be used to market the beers (though it is also possible that Cannon insisted on it as part of his marketing strategy). Since then, many head brewers have put their names, signature and even faces on ‘premium’ products, but it was distinctly unusual at the time.

At launch in 1987, the range included bitter, strong bitter, brown ale, strong brown ale, lager, strong lager, and a stout—an unusually diverse selection at a time when most breweries in the UK restricted themselves to brewing bitter and best bitter, with perhaps a ‘strong ale’ at Christmas.

The picture above featured in a full-page advertisement under the heading ANNOUNCING BRITAIN’S FIRST RANGE OF ENTIRELY NATURAL STRONG BEERS… NO PRESERVATIVES, NO ADDITIVE:

In response to an ever-increasing demand for additive-free products, The Cornish Brewery Company is delighted to announce the launch of their unique range of natural beers. A unique choice of Lager, Bitter, Brown and Stout: a unique choice of strengths: a totally new concept in drinking which will appeal to all beer drinkers. Don’t miss your chance to join the New Age of Steam.

Though some have suggested retrospectively that the beers were ‘bland’ (including Belgian beer expert Joris Pattyn) at the time they offered a refreshing alternative to the market leading stout (Guinness) and brown ale (Newcastle). As such, they found cautious approval from the new class of beer critics, including Michael ‘Beer Hunter’ Jackson, who, in his New World Guide to Beer described ‘a range of well-made all-malt brews’:

They are not Steam Beers in the American sense, and the term was clearly conceived as a marketing device. However, they are made in a way that it unusual in Britain. They have a two-stage primary fermentation, and they are cold-conditioned. The whole range is malt-accented and notably clean-tasting.

* * *

That same year, it seems Anchor Brewing in San Francisco got wind of Newquay Steam and took, or threatened to take, legal action. (We have not been able to find specific details.) In response, Cannon’s ‘Island Trading Company’, which owned the Newquay Steam trademark, took Anchor to court. The intention was to block Anchor’s plan to launch their own Steam Beer on draught in the UK.

With breath-taking nerve, Cannon’s lawyers argued that British customers were used to ordering a ‘pint of Steam’, meaning Newquay Steam bitter, and that another draught beer of the same name would be confusing to them. It was at this time, it seems, that a story for the origin of the name Newquay Steam was contrived: in Cornwall, the lawyers claimed, ‘steam’ is slang for strong beer. We can find no evidence to support that suggestion, and have certainly never heard the phrase in use with that meaning.

Island Trading won their case, holding back the arrival of draught American ‘craft beer’ in the UK.

* * *

The success of Newquay Steam took many by surprise: from a standing start, the equivalent of 35,000 barrels were sold in 1988. (For comparison, London Pride sold 89,000 barrels in 2012-13.)

Cannon put that success down, in large part, to the popularity of Newquay Steam with other UK brewers who wanted to provide a choice of interesting bottled beers in their pubs without importing or buying from their more heavyweight competitors.

John Spicer, a leading drinks market analyst at the time, told us: ‘Everyone in the City of London had high hopes for Newquay Steam and there was a lot of interest in it.’ In their 1989 report on the The Supply of Beer, even the Government’s Monopolies and Mergers Commission recognised that, though beer generally was struggling in the marketplace, Newquay Steam seemed to be bucking the trend.

It couldn’t last.

* * *

Having made such a splash, it is perhaps no surprise that predators began to circle.

In 1991, Boddington’s of Manchester made a hostile takeover bid. Whitbread sold their 15 per cent stake to Boddington’s without a moment’s hesitation, much to Cannon’s annoyance: ‘The cosy relationships of the past have been shattered,’ he told the press.

Will Wallis: ‘The widespread belief was that as we were a direct competitor, they wanted to purchase us and shut us down to remove excess brewing capacity in the trade at that time.’

Michael Cannon, however, saw them off with his customary vigour, though it was a close shave, and left the company reeling and in need of cash.

In May 1991, the Newquay Steam brands were sold to Whitbread, and Will Wallis recalls uncertainty at Redruth:

All artwork, recipes, brewing and processing procedures were passed on to the new owners. At that time we believed that the Newquay Steam range would continue, produced elsewhere in the country using the premises, and raw materials of the new owners.

Then, in July the same year, head brewer Tony Wharmby and a Devenish director, Paul Smith, bought the Redruth brewery for £700,000 and went into business as contract brewers and bottlers.

Devenish continued as a pub company and distributor until, by 1993, Cannon had achieved his aims, and was ready to sell up on his own terms. He had bought his stake of Devenish for £35m in 1986, turned a failing company into one of the hottest brands in the industry, and sold it to Greenalls (Whitbread) for £214m. He ploughed his share of the profit (£26m) into a new pub company, capitalising on changes in the industry following the 1989 ‘Beer Orders.’

The Newquay Steam brand name lived on for short while, but the distinctive swing-top bottles were ditched in favour of cans, with the beer being brewed at Whitbread plants elsewhere in the country. What was a great hope for the industry in 1989 was, by the end, a tarnished brand and a lost opportunity. It seems to have disappeared completely after 1996.

The brewery at Redruth closed for good in 2004, though there are currently plans to redevelop the site, including proposals to install a microbrewery.

Michael Cannon made yet more money running and selling pub chains, and went on to gain notoriety for his purchase and sale of another failing brewery, Eldridge Pope of Dorchester, in 2004. He remains a permanent fixture on ‘rich lists’.

Newquay Steam Beer is fondly remembered my many who popped those ceramic stoppers on beach holidays in the West Country in the late 80s and 1990s, and also by those who appreciated the opportunity to buy a ‘premium’ British lager, stout and brown ale produced by someone other than the ‘Big Six’.

With thanks to Ray Bateman for emailing us about Newquay Steam and encouraging us to look into its history.

Sources

Individuals

- Will Wallis, email, November 2012. (Will now runs http://www.cornwallinfocus.co.uk and http://www.devoninfocus.co.uk.)

- John Spicer, conversation and email, September and November 2013 respectively. (John is one of the authors of Government Intervention in the Brewing Industry.)

- Paul Hampson, email, November 2013.

Books

- CAMRA Good Beer Guide 1988, ed. Neil Hanson, 1987, p30.

- New World Guide to Beer, Michael Jackson, 1988, repr. 1991, p170.

- The Law of Passing-off: Unfair Competition by Misrepresentation, Christopher Wadlow, 2011, p882, cites ISLAND TRADING COMPANY AND OTHERS v. ANCHOR BREWING COMPANY AND ANOTHER R.P.C. (1989) 106 (10): 278-306.

Newspapers and magazines

- ‘Only beer here’, Roger Protz, Guardian, 4 September 1987, p21.

- ‘Contrasting fortunes of two brewers’, Andrew Wilson, Glasgow Herald, 16 December 1987, p1.

- ‘Beers with the taste of bubbly’, Michael Jackson, The Times, 5 August 1988, p18.

- ‘Salut! Cheers! Prosit!’, Roger Protz, Observer, 4 December 1988, supplement, p17.

- ‘Tempus’ on J.A. Devenish, The Times, 21 June 1989, p26.

- ‘Costa UK cheers Devenish’, Ben Laurance, Guardian, 21 June 1989, p11.

- ‘Devenish advances 22% to £14m’, Philip Rawstorne, Financial Times, 13 December 1989, p21.

- ‘Lack of steam as Devenish dips to £3.8m’, Financial Times, 13 June 1990, p24.

- ‘Bitter row brews over beer bid’, Martin Winn, Daily Express, 19 April 1991, p41.

- ‘Boddington presses Devenish on plans for Redruth brewery’, Philip Rawstorne, Financial Times, 3 May 1991, p22.

- ‘Redruth brewery faces closure as Devenish pulls out of brewing’, Ben Laurance, Guardian, 23 May 1991, p15.

- ‘Devenish sells brewery’, The Times, 23 July 1991, p22.

- ‘Judge blocks US brewer from selling draught beer in Britain’, Associated Press, 11 November 1988, AP News Archive, http://www.apnewsarchive.com/1988/Judge-Blocks-U-S-Brewer-From-Selling-Draught-Beer-in-Britain/id-c2324e014dc3dbe74c35048e9bd403d2

- ‘Fuddruckers feast for Cannon’, Rachel Bridge, The Times, 4 August 1998, p23.

- ‘Bristol makes an impact on the Sunday Times Rich List’, Bristol Post, 30 April 2012, http://legacy.thisisbristol.co.uk/Bristol-makes-impact-Sunday-Times-Rich-List/story-15958586-detail/story.html#ixzz2jZWvjRua

- ‘Hoteliers dominate The Sunday Times Rich List 2013’, Janet Harmer, Caterer and Hotelkeeper, 22 April 2013, http://www.catererandhotelkeeper.co.uk/articles/22/4/2013/348222/hoteliers-dominate-the-sunday-times-rich-list-2013.htm#sthash.Ww7P52Sn.dpuf

- ‘Estate of Independents’, Caterer and Hotelkeeper, 19 November 1998, www.catererandhotelkeeper.co.uk/articles/19/11/1998/13983/estate-of-independents.htm

Websites

- ‘Newquay Steam Remembered’, forum thread, Ratebeer.com, 2007, http://www.ratebeer.com/forums/newquay-steam-remembered_79078.htm

- ‘Newquay Steam Bitter’, Oxford Bottled Beer Database, www.bottledbeer.co.uk

- ‘Packaging from the Start’, Paul Hampson, http://hampsonpartnership.blogspot.co.uk/2011/04/from-our-portfolio.html

CAMRA’s What’s Brewing

- ‘Cannon fires into Devenish’, March 1986, p1.

- ‘Devenish shake-up’, July 1986, p1.

- ‘Uproar over polluted pint’, November 1986, p1.

- ‘British brewers must come clean’, Roger Protz, December 1986, p6-7.

- ‘Pure and simple: the German answer’, Brian Glover, December 1986, p7.

- ‘Caught in the rapid Cannon fire’, Brian Glover; ‘All change at Weymouth’, Paul Hathaway; and associated smaller articles, May 1987, p8-9.

- ‘Cornish steams ahead with natural beer’, July 1987, p5.

NOTE ON IMAGES: if you own the copyright on any of the 1986-87 images used in this post and would like either a credit or for them to be removed, contact us at boakandbailey@gmail.com

8 replies on “Newquay Steam: Cornwall’s Own Beer”

My recollection is that the Newquay Steam beers were always perceived as a bit gimmicky, all mouth and no trousers. “Steaming” is of course another term for “drunk” – they’d probably be banned by the Portman Group now.

Devenish never had much of a reputation prior to the Cannon takeover – it’s one of those former family brewers that now seems to have disappeared off the face of the earth.

I remember looking askance when What’s Brewing lauded these beers to high heaven. I tried a couple at the time and at best they could be called “bog standard”. All fur coat and no knickers as we allegedly say up here in ‘t grim north.

As for Michael Cannon and Devenish. I was speaking to a high lavel Greeenalls executive a couple of years aftet they bought the pubs. There had bene plenty of showy investmen tin them but it all seemed to have bene “front of house” – behined the scenes it was all a bit of a shambles. I would say that Cannon’s apotheosis with this sort of approach was the Magic Pub Company which largely comprised tat filled theme pubs done very much on the cheap (or appearing so at any rate). Everything was very short term.

Great article but another thumbs down for the beers. New Quay Brown was the one I saw most often (I wonder how they got away with that name?) and it was dull and sweet.

Around the time Newquay Steam was big I think I was young & impressionable – just getting into beer & a bit taken by the swing-tops & the marketing. I remember liking the bitter, but couldn’t now quite say why! It may have been a bit tame, as some have suggested, but being all-malt & additive free set it aside from many UK beers at the time.

I was very interested to hear about the legal battle with Anchor. In the past I’dd heard industry talk that Anchor were quick to threaten legal action & perhaps unreasonably over-protective of their brands (King&Barnes had a single-hopped “Liberty Ale” that I’ heard Anchor pounced on?). But with Redruth’s seemingly entirely spurious yet successful counter-claim, I can see why Anchor might have fought harder to protect their brands once they were exporting more into the UK.

… @Ed – despite my age, I was still amazed that “Newkie Brown” let them get away with using the name “Newquay Brown”!

I recall these beers being on promotion in the Newcastle University SU c.1989. My early beer geek curiosity was aroused but i don’t recall being particularly enamoured.

About the same time I was buying a rather good Czech lager from a local offy. It came with a plane brown label rather like the Kernels. I wish i knew what this beer was.

Supremely interesting. Oddly, I find the term ‘Steam Beer’ incredibly evocative – although whether I would have *at the time* is another matter.

[…] We wrote a long post about cult Cornish beer Newquay Steam as part of ‘beery long reads‘.(Suggestions for other lost brands or breweries we might research very welcome.) […]