In 1963 Guinness hired Public Attitude Surveys Ltd to compiled research into the attitudes of drinkers towards stout, and the state of the beer market more generally.

The resulting report feels to us like an important document, recording statistics on different types of beer, and different types of drinker, based on gender, social class and attitudes to alcohol.

It’s about Guinness but almost accidentally gives us great insight into the rise of lager, the death of mild, and so on.

Unless we’re mistaken, this is a source that hasn’t previously made its way into the public domain or otherwise been much exploited, though there were some contemporary newspaper reports picking up on its findings. We only have our hands on a copy because it came as part of the collection of Guinness papers we’re sorting through on behalf of the owner.

It begins with a summary of what was learned from previous ‘National Stout Surveys’ carried out in 1952-53 and 1958-59:

Guinness was markedly more dependent on the heavy drinker than Mackeson, the next most successful stout on the market… Recruitment to Guinness was not to any substantial amount from sweet stouts… [And] Guinness was much more dependent on the older drinker – those over 45 – than Mackeson and the other sweet stouts.

This helps us understand what Guinness was worried about: that younger drinkers were turning away from dark, bitter, heavy beers. That’s a problem when your flagship product — more or less your only product — is a dark, bitter, heavy beer.

This is the first big splash from the document. It shows that in the early 1960s women hardly touched draught bitter or mild, and weren’t especially keen on the then fashionable bottled ales either. But lager and stout – two opposite ends of the spectrum you might say – were about equally popular with men and women.

But overall, women drank less of everything: lager might have been popular with women, but women weren’t driving the growing market for lager. “[All] types of beer are much more dependent on the male… though this dependence is least in the case of stouts”, writes the report’s author.

Guinness was for old people; lager, brown ale and bitter were where it was at for the under-thirty-fives, who when they did drink stout, preferred sweeter varieties.

Guinness was for old people; lager, brown ale and bitter were where it was at for the under-thirty-fives, who when they did drink stout, preferred sweeter varieties.

That must have worried Guinness executives — would the younger drinkers of 1963 get the taste as they grew older, or was its constituency dwindling? Would there be no Guinness drinkers by 1980?

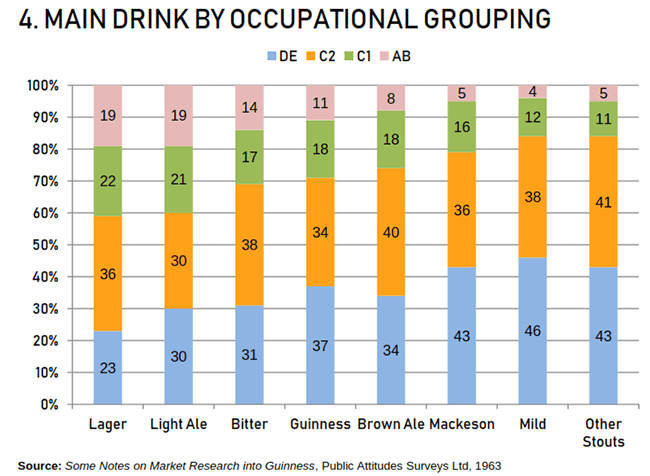

This item refers euphemistically to class, via NRS categories: Ds and Es are working class, essentially; C2s are skilled working class; C1s clerks and junior managers; and As and Bs are the professional classes.

The conclusion of the report from the numbers was that middle class drinkers preferred bitter drinks and lager, while unskilled working class drinkers generally preferred sweeter beers. Guinness, meanwhile, appealed across social groups.

* * *

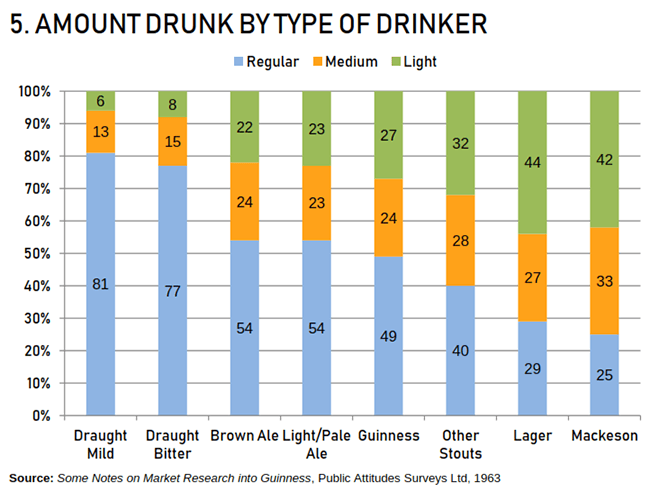

Now, this next section, on types of drinker, gets a bit complicated.

First, for clarity: ‘regular drinkers’ is British English and refers to people who drink frequently/heavily (more than 5.5 pints per week for the purpose of this survey) rather than meaning, as it might in US English, ‘normal drinkers’.

Secondly, there are two sets of figures that are hard to distinguish, and obviously confused the original owner of this document, too: there are sums scribbled all over the page in pencil alongside exasperated annotations: !! ??

The explanatory text doesn’t help much. Item 1, accompanying Chart 5:

The National Beer and Stout Survey 1960-61… showed that whereas 49% of Guinness was drunk by regular drinkers… 54% of light and brown ales were accounted for by such regular drinkers and nearly 80% of draught beers. Only lager and sweet stouts were less dependent on the regular drinkers.

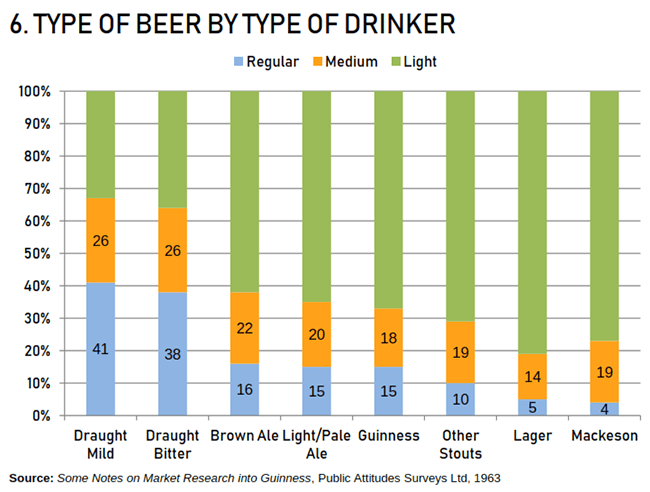

And Item 2, from the text for Chart 6:

The regular drinker… is the modal type of drinker in the draught market; and each one accounts for about two out of every hundred pints of draught drunk. The regular Guinness drinker represents only 15% of all Guinness drinkers and each one accounts for over three out of every hundred pints of Guinness drunk… Now compare the position of Mackeson, where each regular drinker accounts for six out of every hundred pints of Mackeson drunk. Looked at in this way, the recruitment of a regular drinker to Mackeson is more important to them than the recruitment of a regular drinker to Guinness. In other words, it is quite as justifiable to say that Mackeson is uncomfortably deficient in regular drinkers as it is to say that Guinness is dependent on regular drinkers.

Eh? We think we’ve got this straight, at least:

- Chart 5 shows that, e.g., 81 per cent of draught mild sold was drunk by regular (frequent/heavy) drinkers…

- While Chart 6 shows that out of every hundred people identifying themselves as draught mild drinkers, 59 were medium or light drinkers overall.

If you can make better sense of this, or the frustrated Guinness insider who once owned this copy, let us know in the comments below.

The above chart represents a different angle on the same numbers:

The draught drinkers take on average about seven pints per head per week. Guinness drinkers drink 2.7 pints per week. Mackeson drinkers only drink 1.9 pints per week.

Could you conclude from that that Mackeson and Guinness were somewhat better insulated than draught mild and bitter against a trend towards moderate drinking that seemed to be underway at this time?

***

Beyond the purely statistical research, PAS also tried to get to the bottom of why people might choose the drinks they choose – to understand the psychology behind their decisions. They referred to earlier research carried out by the Tavistock Institute of Human Relations on behalf of Guinness in 1959 which suggested three situations in which “a man was likely to use alcohol to relieve… stresses”:

– Reparative: centred on the notion of regular somewhat monotonous duty

– Social: centred on competitiveness

– Indulgent: centred on escapism.

Reparative drinkers, it was suggested, would prefer bitter drinks “reflecting the dourness of their life situation and their solid, responsible attitude towards it”. We were inclined to scoff at this at first – surely people don’t choose a beer based on its symbolic value! – but then we thought, well, there is something in the idea of the no nonsense, no fuss Bitter Drinking Man.

Indulgent drinkers, meanwhile, were thought to prefer sweet drinks – why grimace through bitterness when you can just have comforting fun?

The Guinness angle here: Guinness drinkers were more likely to be ‘reparative’ drinkers, favouring bitterness, while sweet stout fans were indulgent escapists.

And why did women favour stout? PAS Ltd asked a sample of female stout drinkers: “How did you start to drink stout?” Eighty-three per cent of those who responded said it was for their health – as a tonic when run down, to put on weight, after childbirth, and so on.

Where on earth can they have got that idea?

The final section gave some early and inconclusive consideration to the question of draught vs. bottled Guinness, suggesting tentatively that the then relatively new draught Guinness product might be acting as a stepping stone to the bottled version for some drinkers:

If draught Guinness is to have this role then those properties characteristic of Guinness should be present in draught Guinness, but in more moderate measure. Thus it should be a little less bitter, a little less strong, a little less full-bodied than the bottled product.

Could this be where the rot began to set in? As it happens, another document from the collection, produced a decade later, sheds light on this very subject…

2 replies on “The Mother lode: Attitudes to Beer, 1963”

refreshingly free of irritating marketing jargon. I dread to think how the same information would be presented today. As for “dourness of their life situation”, isn’t that what gin is for?

‘PAS Ltd asked a sample of female stout drinkers: “How did you start to drink stout?” Eighty-three per cent of those who responded said it was for their health … Where on earth can they have got that idea?’

As it happens, the “Guinness is Good For You” slogan sprang out of advertising agency research in the 1920s: when the ad people asked consumers why they drank Guinness, they replied: “Because it’s good for me.” The slogan was designed to reinforce a perception people already had – and the idea of stout being “good for you” can be traced back to the 1870s and before.