John Braine’s 1959 novel The Vodi is set in a fictional northern town where every other conversation takes place over a beer, or in a pub.

Of particular interest is the portrayal of a large, modern pub – a theme you might remember comes up in another social realist novel from the same year, Keith Waterhouse’s Billy Liar.

Braine’s treatment is succinct and direct:

[He] didn’t like the Lord Relton very much. It was a fake-Tudor road-house with a huge car park; even its name was rather phoney, an attempt to identify it with the village of Relton to which, geographically at least, it belonged. But, unlike the Frumenty, unlike even the Ten Dancers or the Blue Lion at Silbridge, the Lord Relton belonged nowhere; it would have been just as much at home in any other place in England. It even smelled liked nowhere; it had a smell he’d never encountered anywhere else, undoubtedly clean, and even antiseptic, but also disturbingly sensual, like the flesh of a woman who takes all the deodorants the advertisements recommend.

Pubs in general are presented as a kind of erotic playground, all flirtatious barmaids and “goers” – frustrated wives, lonely war widows and other women no better than they should be. It’s no wonder, then, that the (angry) young men in the book practically live there, talking endlessly about sexual adventures, ambitions and the relative attractions of the women they know.

As for older people, though, Braine also gives notes on the lads’ parents’ drinking habits. Here’s a bit about the protagonist’s family:

[Dick’s] father [preferred] the Liberal Club (one pint of mixed, one large Lamb’s navy rum, every evening at nine-twenty precisely, except Wednesday and Sunday) and his mother rarely touched alcohol at all, much less visited a pub.

(‘Mixed’ is a blend of mild-and-bitter.)

There’s also a surprising amount of drinking at home, given the idea sometimes conveyed in commentary that this is a new and disturbing phenomenon threatening pubs.

Dick and his father share bottles of Family Ale after they’ve done the weekly accounts for the shop, and Mr Coverack, Dick’s best friend Tom’s Dad, is an expert pourer of bottled Tetley’s Bitter:

He opened another bottle of beer and filled his glass with his usual competence; none frothed over and there was exactly the right amount of head on it to make it immediately drinkable. Tom had once commented to Dick with some bitterness on this trait of his father’s. “My Old Man,” he said, “can do any little thing you can mention, from mending a switch to pouring a glass of beer, like a professional. It’s the big things, the important things, he messes up.”

There is even a brief description of a specific beer – quite unusual in fiction generally. It’s in a passage set in a pub which is filling up with the evening crowd, developing a warm atmosphere and buzz:

The sun was setting now; the faces at the far side of the room glimmered palely, the faces nearest the fire were dramatically lit in red and black, the bitter in the tankard of the old man at the table next to Dick’s was changed from straw-yellow to near-amber sown with glittering specks of gold; when the girl, bringing in Tom’s round, switched on the light there was an element of annoyance in the glances directed for a split-second towards her; the transition from an atmosphere as cosy as a Victorian ballad had been too abrupt and the room seemed, during that transition, drab and mean.

Straw-yellow is interesting with the history of northern beer in mind but this passage is also a reminder of the importance of light in both the mood of a pub and the appearance of any given beer.

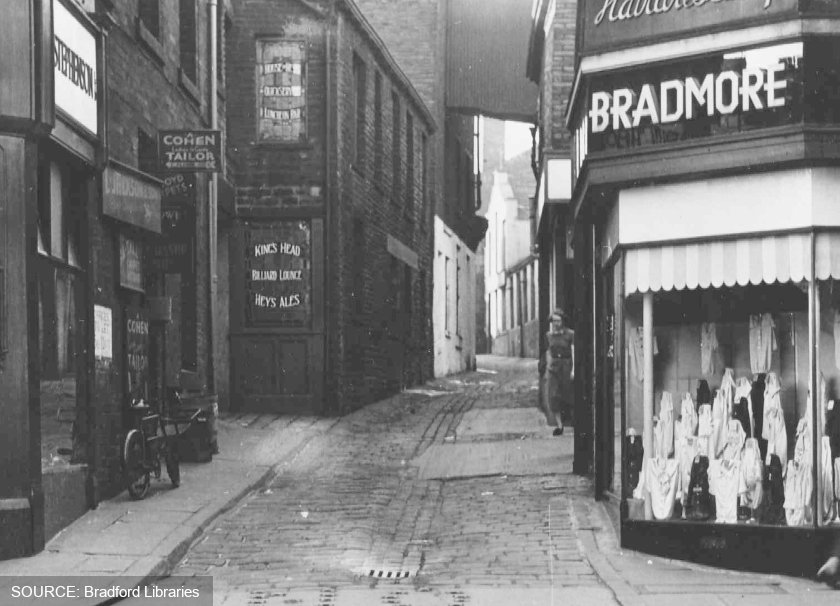

We won’t go through every pint, bottle and saloon bar in the book, but take our word for it, there are plenty – further evidence that acknowledging the pubs existence of pubs was a key factor in giving post-war British fiction its sense of startling realism.

For more on inter-war pubs, roadhouses and the post-war response to them, check out our book 20th Century Pub.