During the last few months, we’ve acquired a few obscure second-hand books and magazines from charity shops and on Ebay.

Though none of them is exactly essential for the scholar of beer and pubs, each has some little nugget or other.

Pubbing, Eating & Sleeping in the South West is a paperback guidebook first published in 1972. Our faded copy (still lurid enough to damage the eyeballs of anyone who might glance at the cover without suitable protection) is the 1974 edition, and cost us 10p less than the original cover price.

Pubbing, Eating & Sleeping in the South West is a paperback guidebook first published in 1972. Our faded copy (still lurid enough to damage the eyeballs of anyone who might glance at the cover without suitable protection) is the 1974 edition, and cost us 10p less than the original cover price.

It’s not a deep or complex piece of work but does give details of the beer, food and facilities at various pubs in Somerset, Devon and Cornwall. Many listings are accompanied by line drawings like this one of the Ship Inn, Mevagissey:

There are also a couple of nice vintage advertisements (‘Take it Easy! Worthington E’) and the restaurant guide is an added bonus for those with a desire to time travel to the land of prawn cocktails and steakhouses.

We haven’t finished digesting Inn & Around: 250 Whitbread pubs (1974) but have already found lots to enjoy.

We haven’t finished digesting Inn & Around: 250 Whitbread pubs (1974) but have already found lots to enjoy.

It was, we suspect, intended as a ‘stopper’ for the Campaign for Real Ale’s own Good Beer Guide which was first published in paperback in the same year, but it’s hard to imagine anyone being so loyal to one large, rather unpopular brewery that they’d want a guide to only their pubs.

Those who cling to a particular vision of the pub as a Victorian-Edwardian, essentially male space, designed for hard drinking, will find here evidence of where it all ‘went wrong’: “The pub today is a place for family entertainment. And — with the increasing spread of children’s rooms and beer gardens — that means all the family.”

Whitbread’s flagship post-war pubs are given plenty of coverage alongside established classics such as (yet again) the George Inn at Southwark. This one was named after the Daily Express cartoonist:

It doesn’t appear to be there any more. How many of these flat-roofed, wood’n’plastic boxes survived more than twenty years?

As well as illustrations, there are also some splendidly groovy colour photographs.

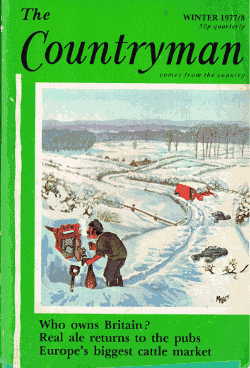

Finally, there’s the Winter 1977/78 edition of the Countryman magazine, which contains an article by Michael Dineen called ‘Real Ale Returns to the Pubs’, as well as a short spread of photos of Hook Norton brewery by John P. Crook.

There isn’t much new in the tale as told here, but it does give a concise account of the big brewers’ response to CAMRA:

However, one of the acceptable facets of capitalism is that it can turn criticism to its own advantage. Benefit from the strictures…. The result is that many brewers have appropriated CAMRA’s enviable nationwide propaganda, calling their cask-conditioned ales ‘real’ or attempting in other ways to cash in on the publicity by naming so evocatively that drinkers’ memories are stirred again by words like old, tap, genuine, Burton and fine.

The conclusion of the article could be read as a comment on our post from yesterday:

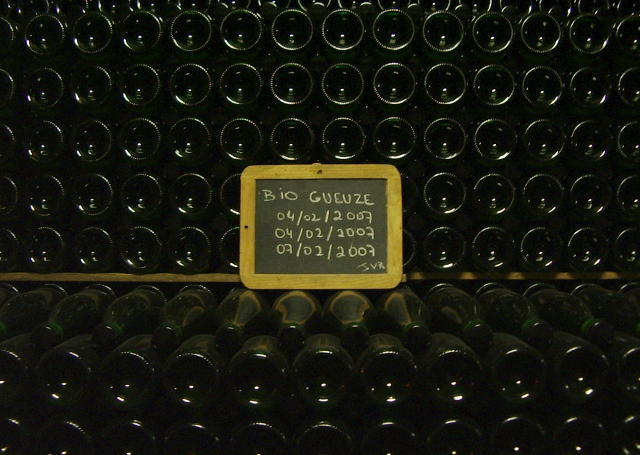

[CAMRA] want quality with tradition… [They] may also be yearning for the glorious uncertainties of, say, La Romaneé Conti, the rarest and finest of Burgundy’s red wines which… stubbornly refuses to be defined scientifically; which may one year be the stuff of dreams and memories and the next, just another wine. [Real ale] has something of that uncertainty.

Every now and then, someone asks, ‘

Every now and then, someone asks, ‘

Michael Pollan’s book is a mix of history, philosophy, personal memoir and cookbook, which amounts to an extended pep talk: cook more! Eat more dirt!

Michael Pollan’s book is a mix of history, philosophy, personal memoir and cookbook, which amounts to an extended pep talk: cook more! Eat more dirt!

We don’t know Steele or anything about him and went into IPA: brewing techniques, recipes and the evolution of India pale ale expecting something, after the house style of his employers, ‘aggressive’ and ‘passionate’ in style. In fact, the tone is quietly scholarly, and reassuringly deferential to researchers and historians who have gone before, such as Mark Dorber, Ron Pattinson and Martyn Cornell. Nor is there any sense that this is a publicity opportunity for Stone: where they are mentioned, it is only where it might have seemed crazy to omit them.

We don’t know Steele or anything about him and went into IPA: brewing techniques, recipes and the evolution of India pale ale expecting something, after the house style of his employers, ‘aggressive’ and ‘passionate’ in style. In fact, the tone is quietly scholarly, and reassuringly deferential to researchers and historians who have gone before, such as Mark Dorber, Ron Pattinson and Martyn Cornell. Nor is there any sense that this is a publicity opportunity for Stone: where they are mentioned, it is only where it might have seemed crazy to omit them.