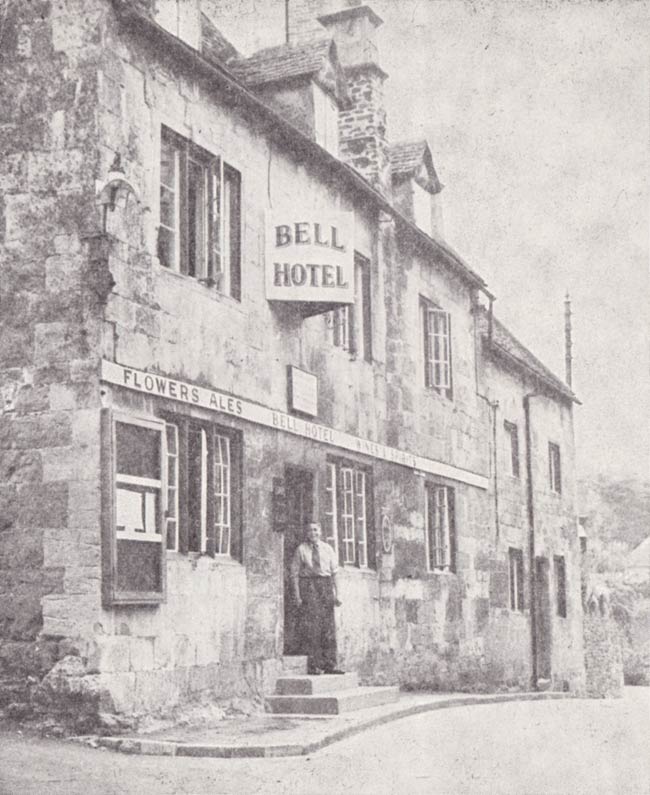

Molly Figgures was born Gwendoline Mary Barrett in Blockley, on the Gloucestershire-Worcestershire border, in 1907. When she was a child, her father, Ernest Alfred, took over the running of the Bell Inn at Blockley where she would live and work for the next 50 years.

We’ve often lamented the dearth of first-hand accounts of pub life in the 20th century.

Fortunately for us, Molly was encouraged by local historian Norah Marshall to write down her stories of life at the Bell.

What she wrote was published under the cryptic title Over the Bones by Blockley Antiquarian Society in 1978.

These local history publications aren’t always riveting, let’s be honest. This one is genuinely brilliant, though, not because Molly is a great writer but because The Bell, and Blockley, sound… mad.

Consider these two paragraphs in which Molly recollects some of the regulars from her childhood days:

We had some delightful old age pensioners who were customers. There was ‘Shover’ Eden, he came along to fetch his paper and always called for a drink every morning, which was a pint of bitter. He said that The Bell was the Doctor’s surgery and he’d come for his medicine! There was Ted Beachey who had a half of bitter. His wife was the local midwife. She made humbugs and aniseed sweets which were in ‘pennyworths’ wrapped in newspaper. Often halfway through eating one you would find a dead wasp in the centre! Ted frequently brought some along for us. You had to get the newspaper off too before you could eat them. However, we did not mind so long as we had sweets to eat! I only had 1d a week to spend so being free they were very welcome.

There was also a Mr. Freeman and he had a tame fox which he brought with him. Fred Hitchman was a very regular customer in the evenings and he always smoked a pipe so of course he was honoured with a spittoon which he proudly had between his feet so that he could spit in comfort! It was not a very pleasant job to empty these spittoons and we had to buy sawdust by the sackful from Butlers saw-yard at Draycott to put in them. Sometimes the spittoons were turned into a form of entertainment when a well-known character, who had served in the Navy, would go down on his knees and slide them around the floor accompanied by an appropriate song. This was known as Holy Stoning.

So, to summarise, we’ve got boiled sweets with wasps in them, a tame fox, and curling with spittoons – this is some real folk horror stuff.

She also describes various moments of arguing and fighting, including the occasion when ‘Badgie Mayo’ got into a scrap with another customer. Because Badgie had lost an arm in WWI, the other man agreed to tie an arm behind his back so their dust up in the pub garden would be fair.

The very best part might be her account of throwing out a customer who was rude to her mother:

He called my Mum by a name of which I disapproved, so I ordered him out and made him go and I followed him and told him never to come in again, and he didn’t.* My Mum said this was the first time she had seen “Our Moll” in a temper, which goes to show what one can do.

* He is dead now. I hope he went to the right place!

There are some lovely details about the evolution of the pub. First, there’s the installation of what Molly calls a ‘snug’ but which sounds more like what would usually be called a lounge, with an electric bellpush for service and a penny surcharge per drink.

Then there’s the acquisition, after World War II, of a television, which caused great excitement in the village. One local, Molly says, became a fixture at the pub, lingering for hours over a half so he could watch whatever was on. Until he got his own TV, that is, when he stopped coming to the pub altogether. If we’d made that up, you might think it was a bit heavy handed.

There’s some great stuff about booze, obviously, lots of it a reminder of the freedom a remote village offered when it came to obeying the letter of the law.

For example, Molly’s mother made rhubarb wine while Bert, Molly’s husband, produced plum. Strictly against the law, you could order your cider ‘with’ and get a shot of wine added to the glass to give it extra oomph.

(Again, mixing and blending was absolutely normal until quite recently; it’s not a weird modern development.)

As for beer…

All the beer was drawn from the wood and it was twenty walking steps each way to the cellar to fetch each drink so of course some was spilt and sometimes my Mum would spill more than usual and there was usually someone who complained; but on the whole people were very good. Some would say “Mrs., my glass ain’t full” so my Mum would take a swig out of the glass and say “It is full now” and no more was said. I could carry four full glasses with handles in each hand and not spill much. My Mum refused to put pumps in until 1951 when my brother talked her into having them. Then she said that she wished she had had them installed years before! Unfortunately she only lived for two years after so she did not benefit much… Sometimes a customer would say the beer was flat, and Kate (my Mum) would take it back to the cellar to “change it” and all she did was make another head on it and take it back and the customer would say “Ah! that’s better” – So what!

That last point is yet more evidence of the confusion between foamy beer and beer in good condition.

One of the appendices provides a list of nicknames for pub regulars including Buffud, Chicken, Grunter, Gubbins, Jambox, Sneezer, Waggy and Yatty. Molly’s husband, Bert, was known as Pur-Pur because he had a stammer.

And the title? In 1970, after Molly’s retirement, the pub was converted into four flats and during building work, two skeletons were found beneath the floor. “It was fun really,” writes Molly: “I kept meeting people who pulled my leg and said they didn’t think I was like that!” The bones turned out to be of medieval origin, of course.

If you want to read more, Molly’s text is available as part of a collection called A Third Blockley Miscellany at £6.50 from Blockley Heritage Society.