From about 1960 onwards,The Financial Times repeatedly ran articles attempting to explain the boom in lager sales in the UK, and debating whether they would keep rising, and how far. One of the reason most often given was the weather. A hot summer in 1959 saw imports of lager rise to a peak of 270,000 barrels, after which point lager production in Britain took off in earnest.

One British lager brewery reports that half its production is sold in the 17-week summer season, and another that it sells three and a-half times as much in its best months as in the bleak mid-winter. (FT, 14 May 1959.)

Guinness reckon Harp Lager acquires an increasing market share in the summer and manages to keep its new customers loyal in the winter months, albeit in reduced volume. (FT, 10 August 1974.)

As those quotations suggest, breweries certainly believed hot weather made a difference, and some reports suggest that lager briefly took a 40 per cent share of the market during the heat wave of 1976.

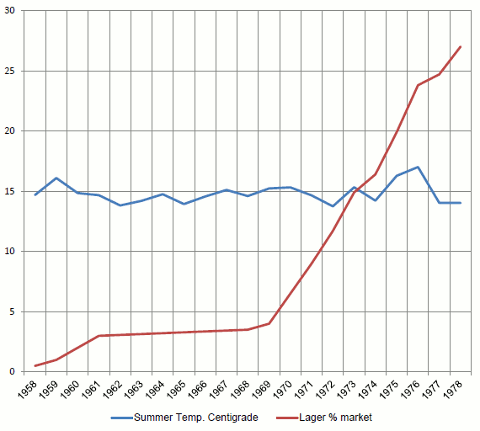

In our amateurish way, we’ve mapped percentage share of the market for lager against mean summer temperatures as recorded by the Met Office (see above). We can see a bump around the 1959 heat wave; again with the warm summers of 1969 and ’70; and once again with hot weather in 1975 and ’76.

On the other hand, commentators from the CAMRA camp were of the view that marketing was also a major driver, as expressed by Roger Protz in his 1978 book Pulling a Fast One, which you might have noticed we’re finding to be a gold-mine at the moment. He says lager advertising budgets were £268,000 in 1967; £3.2 million in 1974; and £9.8 million in 1977. Here are those budgets (in ‘millions of pounds’) plotted against sales:

Now, that looks to us like marketing budgets rose in response to the market share for lager increasing: it was about making sure that, if people were demanding lager, it was your lager they bought.

Hmm. Ponder ponder. At some point, we’ll have to look at stats on foreign holidays mapped against lager sales, too.

DISCLAIMER: This post is strictly for the purposes of entertainment. These cobbled together numbers and graphs not to be used as a buoyancy aid.